Part 3 of 3: Why do we use oak in winemaking? The red edition…

The use of oak in winemaking is so much more about structure than flavour:

Red wines are aged (not “fermented”) in oak. The barrels are filled after fermentation and extended skin contact are completed—this is 20-30 days post-harvest. We try to get the wine to barrel right after draining & pressing off skins.

As red wines age, their tannin molecules, which can be astringent and grippy when young, slowly join together to form larger, softer, smoother molecules, (think Lego—how much does each little piece hurt your feet?? but once it’s assembled into a masterpiece—no pain just pleasure!).

The oak of the barrels contains wood tannins, which react with the tannins from the wine to help start and to speed this process of “structuring” these tannins. The newer the barrel, the more of this chemical reaction.

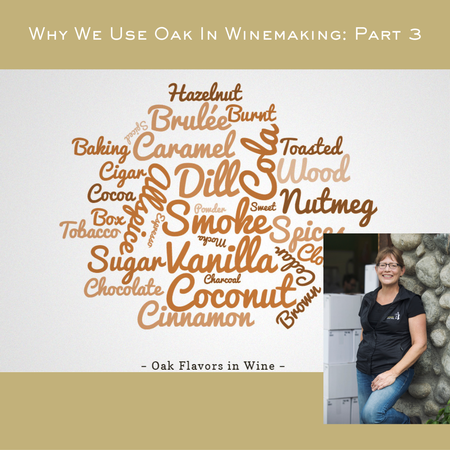

When barrels are toasted, there is less wood tannin available for structuring, and more flavour contribution—vanilla, caramel, spice etc flavours. The heavier the toast, the more bourbon-like the aroma and flavour becomes. An additional option is length of time toasted, with “medium-long” tending to enhance wines of a more elegant style and destined for longer barrel-aging. At Hillside, we use only light to medium toast levels and most often the barrel heads are not toasted at all.

The red wines all go through a secondary fermentation, called Malo-lactic fermentation. A species of bacteria converts malic acid, the predominate acid in apples which is also found in grapes, to lactic acid, the predominate acid in milk. The latter is a much weaker acid, so this fermentation softens the wine and also prevents the possibility of this happening later in the bottle creating carbon dioxide gas and causing pressure to build. This fermentation is started by a culture that we add and can be carried out in tank or barrel. We find that getting the wine to barrel prior to malo-lactic fermentation tends to create a wine of greater mid-palate flavour and structure.

We test the barrels periodically to assess whether this fermentation is finished, whereupon we rack the barrel (pump out the wine but leave the sediment), analyse the wine and refill the sanitized (with steam) barrel. This is called a ‘rack and return’ and, depending on the variety, will be repeated every 3 to 5 months.

Most of our red wines are 100% barrel-aged. The percentage of new oak barrels used is determined by the variety and style of wine, generally 20% to 60%, with the balance of the barrels being an assortment of 2nd-fill up to 7th-fill barrels. This is designed to ensure complexity and integration with the wine.

New barrels serve as trials each year of: new forests, new coopers (barrel makers), new toast levels etc. Each effectively becomes a 225 L trial. These new barrels are always racked out and back individually rather than as groups and sampled so that we can assess them and the development of the wine through the aging process. For a blend, like Mosaic, we put our best wines into an assortment of new barrels so that we have a wide range of options to select from when it comes time to complete the blend.

How long do we keep a barrel? After 3 years a “white” barrel gets shifted to the red barrel program. Both red and white barrels are then used for about 7 years or “fills”, which refers to the number of times a barrel has been filled with a new vintage wine. After about 4 years there is little flavour contribution from the wood, but we do see changes by virtue of time spent in a small wooden vessel. Barrel samples are tasted frequently, and once a barrel seems to no longer be enhancing the wine, ie the wine tastes/smells the same as wine stored in a tank, the barrel becomes a planter (or platter, or furniture etc). Any barrel that is questionable is immediately culled, regardless of its age.

Use of barrels in winemaking requires exhaustive attention and careful evaluation, lots of tasting and very good record-keeping. I’m exhausted just writing about it…